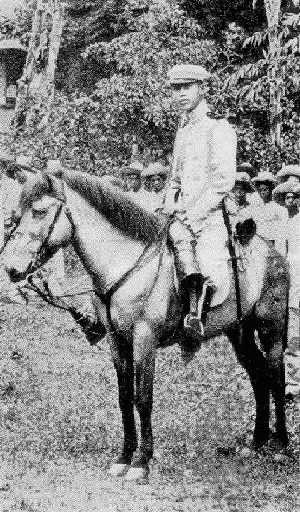

Today is the 160th birth anniversary of Marcelo H. del Pilar, one of the leaders of the Propaganda Movement.

Below is a brief biographical sketch of the bulaqueño native written by Carmencita H. Acosta from the 1965 book Eminent Filipinos which was published by the National Historical Commission, a precursor of today’s National Historical Commission of the Philippines (recently known as the National Historical Institute).

Yeyette in front of Marcelo H. del Pilar's monument in Plaza Plaridel (Remedios Circle), Malate, Manila. This monument used to be in front of nearby Manila Zoo. Fellow Círculo Hispano-Filipino member and Heritage Conservation Society president Gemma Cruz de Araneta (a descendant of Rizal's sister María) suggested the transfer of this monument to this site. It was done last year under the guidance of Mayor Alfredo Lim.

MARCELO H. DEL PILAR

(1850-1896)“The most intelligent leader, the real soul of the separatists…” — these were the words used by Governor General Ramón Blanco, chief executive of the Philippine colony, in describing Marcelo H. del Pilar. A master polemist in both the Tagalog and Spanish languages, del Pilar was the most feared by the Spanish colonial authorities.

Del Pilar was born in Bulacán, Bulacán on August 30, 1850, the youngest of ten children of Julián H. del Pilar and Blasa Gatmaitán. His father had held thrice the post of gobernadorcillo in their home town. Del Pilar studied at the Colegio de San José in Manila and at the University of Santo Tomás; at the age of thirty he finished the course in law. He devoted more time to writing than in the practice of his profession because in the former he saw a better opportunity to be of service to his oppressed country. His oldest brother, Father Toribio H. del Pilar, a Catholic priest, had been deported along with other Filipino patriots to Guam in 1872 following the Cavite Mutiny.

He founded the Diariong Tagalog in 1882, the first daily published in the Tagalog text, where he publicly denounced Spanish maladministration of the Philippines. His attacks were mostly directed against the friars whom he considered to be mainly responsible for the oppression of the Filipinos.

In 1885, he urged the cabezas de barangay of Malolos to resist the government order giving the friars blanket authority to revise the tax lists. He instigated the gobernadorcillo of Malolos, Manuel Crisóstomo, to denounce in 1887 the town curate who violated government prohibition against the exposure of corpses in the churches. In the same year, he denounced the curate of Binondo for consigning Filipinos to poor seats in the church while assigning the good ones to Spanish half-castes.

On March 1, 1888, the populace of Manila staged a public demonstration against the friars. Led by the lawyer Doroteo Cortés, the demonstrators presented to the civil governor of Manila a manifesto entitled “¡Viva España! ¡Viva la Reina! ¡Viva el Ejército! ¡Fuera los Frailes!“. This document, which had been signed by eight hundred persons, was written by Marcelo H. del Pilar. It enumerated the abuses of the friars, petitioned for the deportation of the archbishop of Manila, the Dominican Pedro Payo, and urged the expulsion of the friars.

It was because of his having written this anti-friar document that del Pilar was forced to exile himself from the Philippines in order to escape arrest and possible execution by the colonial authorities.

“I have come here not to fight the strong but to solicit reforms for my country,” del Pilar declared upon arrival in Barcelona, Spain. La Soberanía Monacal en Filipinas (Friar Supremacy in the Philippines) was among the first pamphlets he wrote in Spain. The others included Sagót ng España sa Hibíc ng Filipinas (Spain’s Answer to the Pleas of the Philippines), Caiigat Cayó (Be Like the Eel) — del Pilar’s defense of Rizal against a friar pamphlet entitled Caiiñgat Cayó denouncing the Noli Me Tangere.

Del Pilar headed the political section of the Asociación Hispano-Filipina founded in Madrid by Filipinos and Spanish sympathizers, the purpose of which was to agitate for reforms from Spain.

In Madrid, del Pilar edited for five years La Solidaridad, the newspaper founded by Graciano López Jaena in 1889 which championed the cause for greater Philippine autonomy. His fiery and convincing editorials earned from him the respect and admiration of his own Spanish enemies. “Plaridel” became well-known as his nom de plume.

In November, 1895, La Solidaridad was forced to close its offices for lack of funds. Del Pilar himself was by then a much emaciated man, suffering from malnutrition and overwork. He was finally convinced that Spain would never grant concessions to the Philippines and that the well-being of his beloved country could be achieved only by means of bloodshed — revolution.

Weakened by tuberculosis and feeling that his days were numbered, he decided to return to the Philippines to rally his countrymen for the libertarian struggle.

But as he was about to leave Barcelona, death overtook him on July 4, 1896.

His passing was deeply mourned by the Filipinos for in him they had their staunchest champion and most fearless defender. His death marked the passing of an era –the era of the Reform Movement– because scarcely two months after his death, the Philippine Revolution was launched.

I am not really a big fan of Marcelo H. del Pilar, especially when I learned that he was a high-ranking Mason. Besides, I believe that what he fought for would not equate to heroism. He was, to put it more bluntly, another American-invented hero. The American government, during their colonization of the Philippines, virtually influenced the Philippine puppet government to recognize “heroes” who fought against Spain.

But a closer observation on Marcelo’s life will reveal that, like Rizal and other Filipino “heroes” of his generation, he never fought against Spain. They fought against the Church, the sworn enemy of their fraternity (Freemasonry).

What really captivated me about Marcelo is his heartbreaking fatherhood. Since I am a father of four, I can empathize with his sorrowful plight.

A few years ago, when Yeyette and I had only one child (Krystal), and we were still living in a decrepit bodega somewhere in Las Piñas, I happened to stumble over Fr. Fidel Villaroel’s (eminent historian and former archivist of the University of Santo Tomás) monograph on del Pilar — Marcelo H. del Pilar: His Religious Conversions. It was so timely because during that time, I had just gone through my own religious conversion, having returned to the Catholic fold after a few years of being an atheist and agnostic.

In the said treatise by Fr. Villaroel, I learned of del Pilar’s anguish over being separated from his two daughters, Sofía and Anita. Due to his radical activities as an anti-friar, as can be gleaned in Acosta’s biographical sketch above, del Pilar escaped deportation. He left the country on 28 October 1888, escaping to Hong Kong before moving to Spain. And he never saw his little kids and his wife ever again.

Sofía was just nine years old at the time of his escape; Anita, one year and four months. Father Villaroel couldn’t have written this painful separation better:

Month after month, day after day, for eight endless years, the thought of returning to his dear ones was del Pilar’s permanent obsession, dream, hope, and pain. Of all the sufferings he had to go through, this was the only one that made the “warrior” shed tears like a boy, and put his soul in a trance of madness and insanity. His 104 surviving letters to the family attest to this painful situation…

…He felt and expressed nostalgia for home as soon as he arrived in Barcelona in May 1889, when he wrote to his wife: “It will not be long before we see each other again.” “My return” is the topic of every letter. Why then did he not return? Two things stood in the way: money for the fare, and the hope of seeing a bill passed in the Spanish Cortes suppressing summary deportations like the one hanging on del Pilar’s head. “We are now working on that bill.” “Wait for me, I am going, soon I will embrace my little daughters, I dream with the return.” How sweet, how repetitious and monotonous, how long the delay, but how difficult, almost impossible!

Here are some of those heartbreaking letters (translated by Fr. Villaroel into English from the Spanish and Tagalog originals) of Marcelo to his wife (and second cousin) Marciana “Chanay” del Pilar and Sofía:

In 1890: I want to return this year in November (letter of February 4); Day and night I dream about Sofía (February 18), I will return next February or March (December 10).

In 1891: It will not be long before I carry Anita on my shoulders (January 22); Sofía, you will always pray that we will see each other soon (August 31).

In 1892: If it were not for lack of the money I need for the voyage, I would be there already (February 3); I am already too restless (March 2); I feel already too impatient because I am not able to return (April 14); This year will not pass before we see each other (May 11); Be good, Sofía, every night you will pray one Our Father, asking for our early reunion (September 14; it is interesting to note that del Pilar advised her daughter to pray the Our Father despite his being a high-ranking Mason –Pepe–); Don’t worry if, when I return, I will be exiled to another part of the Archipelago (November 9).

In 1893: Who knows if I will close my eyes without seeing Anita (January 18)!; My heart is shattered every time I have news that my wife and daughters are suffering; hence, my anxiety to return and fulfill my duty to care for those bits of my life (May 24); I always dream that I have Anita on my lap and Sofía by her side; that I kiss them by turns and that both tell me: ‘Remain with us, papá, and don’t return to Madrid’. I awake soaked in tears, and at this very moment that I write this, I cannot contain the tears that drop from my eyes (August 3); It is already five years that we don’t see each other (December 21).

In 1894: Tell them (Sofía and Anita) to implore the grace of Our Lord so that their parents may guide them along the right path (February 15); Every day I prepare myself to return there. Thanks that the children are well. Tears begin to fall from my eyes every time I think of their orfandad (bereavement). But I just try to cure my sadness by invoking God, while I pray: ‘Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven’ I am the most unfortunate father because my daughters are the most unfortunate among all daughters… I cannot write more, because tears are flowing from my eyes aplenty (July 18); We shall meet soon (December 5)

I have to admit, reading these letters never fail to move me to tears because I, too, have experienced the same orfandad and the longingness for a father. It is because I have never lived with my dad for a long time since he was always overseas. When we were young, he only stayed with us for a couple of weeks or a few months. And my dad was a very silent man.

His work overseas, of course, was for our own benefit. But the price was depressing: we’ve been detached from each other forever. Whenever he comes home to us, my dad was like a total stranger to me. Especially now that I have my own family and I rarely see him nowadays. No, we are not in bad terms (although I know that he still resents the fact that I married at a very early age). But we are simply not close to each other because of those years of separation and lack of communication. I do not know him, and he doesn’t know me. We do not know each other personally. But I know for a fact that my dad loved us dearly, and that he experienced the same anguish experienced by del Pilar. I’ve read some of dad’s letters to mom, and in those letters he expressed the same desire to come home with us and stay permanently. But nothing like that happened.

The same thing with del Pilar. After all those patriotic talk and nationalistic activities, nothing happened. His sacrifice of being separated from his family was, sadly, all for naught…

When he died a Christian death in Barcelona (yes, he also retracted from Masonry shortly before he passed away), he was buried in the Cementerio del Oeste/Cementerio Nuevo where his remains stayed for the next twenty-four years. Paradoxically, a renowned Christian member of the Philippine magistrate, Justice Daniel Romuáldez, made all the necessary procedures of exhuming the body of del Pilar, one of the highest-ranking Masons of the Propaganda Movement. His remains finally arrived on 3 December 1920. He was welcomed by members of Masonic lodges (perhaps unaware of del Pilar’s retraction, or they simply refused to believe it), government officials, and his family of course.

Sofía by then was already 41; and del Pilar’s little Anita was no longer little — she was already 33.

Anita was very much traumatized by that fateful separation. Bitter up to the end, she still could not accept the fact that her father chose the country, ang bayan, before family. An interesting (and another heartbreaking) anecdote is shared by Anita’s son, Father Vicente Marasigan, S.J., regarding her mother’s wounded emotions:

[My] first flashback recalls April 1942. Radio listeners in Manila had just been stunned by the announcement of the surrender of Corregidor. There was an emotional scene between my father, my mother, and myself. My mother was objecting to something my father wanted to do ‘para sa kabutihan ng bayan’. My mother answered, ‘Lagi na lang bang para sa kabutihan ng bayan?’ [‘Is it always for the good of the country?’] And she choked in fits of hysterical sobbing. All her childhood years have been spent in emotional starvation due to the absence of ‘Lolo’ [Grandfather] Marcelo, far away in Barcelona sacrificing his family para sa kabutihan ng bayan.

“The second flashback is rather dim in memory. I was then two years old, in December 1920. I think I was on board a ship that had just docked at the [Manila] pier, carrying the remains of Lolo Marcelo. All our relatives from Bulacán were present for the festive occasion. Some aunt or grandaunt was telling me how proud and happy I must be. I did not understand what it meant to feel proud, but I knew I was unhappy because I felt that my mother was unhappy. In the presence of that casket of bones, how could she forget the emotional wounds inflicted on her by her father ‘para sa kabutihan ng bayan’ [for the good of the country]?

History is not just about dead dates, historical markers, and bronze statues of heroes. It has its share of eventful dramas and personal heartbreaks. And this is one heartbreak that I will never allow my children to experience.

To all the fathers who read this: cherish each and every moment that you have with your children.