I wonder: if the Sandiganbayan did not issue a hold departure order against Senator Jinggoy Estrada, would the latter have left the country to escape allegations of his involvement in the telenovela that is the PDAF scandal?

Meanwhile, another co-accused, Senator Ramón “Bong” Revilla, Jr., openly declared that he will not leave the country and will squarely face the charges against him.

Both senators, despite their ordeal, are still determined to pursue their political plans in the next national election on 2016. As always, “public service” is their mantra, nay, excuse for doing so. But in fairness to them, their decision to stay put in the country rather than escape means that there is indeed an intention for them to clear their names, that they could be, perhaps (and just perhaps), innocent of the charges filed against them. We are then reminded of an incident not too long ago of a former senator, Pánfilo “Ping” Lacsón, who sneaked out of the country rather than face the charges against him in connection to the grisly murder of publicist Salvador Dacer and his driver Emmanuel Corbito 14 years ago. Rather than fight it out tooth and nail, he opted for the safe way out: by flying out of the country (his ordeal later on inspired a film). On the other hand, it is difficult to blame the former Director-General of the Philippine National Police (who once declared that he hated politics and politicians) for he was up against a formidable wall: the Arroyo Administration.

These three lawmakers’ varying decisions on how to deal with high-profile court cases now remind us of how our national hero, whose birthdate falls today, comported himself in times of crisis. We all know how José Rizal got himself into trouble when he joined Freemasonry and started attacking the friars through his writings, particularly his novels and essays. During his first trip to Europe, the Calambeño wrote and published there his first novel, Noli Me Tangere. It was published in early 1886, and one of the first copies was sent to his Austro-Hungarian BFF, Ferdinand Blumentritt. Copies were subsequently sent to Filipinas.

Rizal and Blumentritt met only once, but they had been sending each other tons of letters for many years since 1886 (the last of this snail-mail correspondence was written from Rizal’s Fort Santiago cell on the eve of his execution); in an age when there was still no Internet and electricity, we can say that the two formed part of an earlier generation of social media users. Even though they were miles apart, they had formed a kindred bond, like that of brothers. So when Blumentritt finished reading Rizal’s first novel, alarm struck his heart for he realized the potential danger caused by his dear Filipino friend’s pen. He advised Rizal to just stay in Madrid for good and from there continue his Propaganda activities.

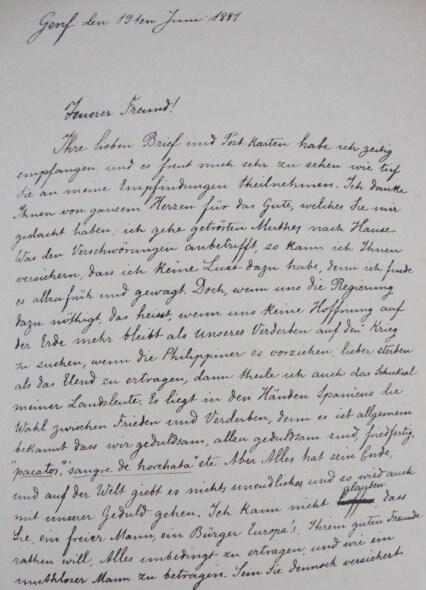

Rizal responded to Blumentritt. In a letter dated 19 June 1887, the patriot wrote:

Su consejo de quedarme en Madrid y escribir allá es muy benévolo; pero no puedo ni debo aceptarlo. No puedo soportar la vida en Madrid; allá todos somos “vox clamantis en deserto”; mis parientes quieren verme y yo quiero verlos también; en ninguna parte la vida me es tan agradable como en mi patria, al lado de mi familia. Todavía no estoy europeizado como dicen los filipinos de Madrid; siempre quiero volver al país de mis aborígenes. “La cabra siempre tira al monte”, me dijeron.

(MY TRANSLATION: Your advice for me to stay in Madrid and write from there is very kind of you, but I cannot even accept it. Life is difficult in Madrid. All of us there are but “vox clamantis in deserto”.* My relatives preferred seeing me and I feel the same way. In no place is life as nice as the one in my country, with my family right by my side. I’m still not Europeanized, as Filipinos say in Madrid. I always want to return to my native country. As they say, “the goat always goes to the mountain”.**)

Did you know? Rizal wrote in excellent German. A few years ago, I purchased volume 5 of the Epistolario Rizalino, composed of two parts, from eminent historian Benito Legarda, Jr. This letter of Pepe Rizal to his German-speaking penpal, Ferdinand Blumentritt, was written on the day the former turned 26, and it appears in the Epistolario’s first part.

The letter, originally in German, was written from Geneva, Switzerland. It was a long one and covered other topics. But the above lines stood out from the rest of the letter’s content as having more heart. It illumined our national hero’s affection not only for his country but for his family as well. We are accustomed to hear about Rizal the Patriot but rarely about Rizal the Family Guy. Of course, his courage speaks volumes here, something to be marveled at (a decade later, however, at the outbreak of the Tagalog rebellion, Rizal was singing a different tune: there was no more swagger left in him when he set sail to Cuba, but that’s another story and matter).

Rizal did not even remind Blumentritt in that letter that it was his birthday; anyway, birthdays were not celebrated back then as they are celebrated today (perhaps that fact could be another interesting topic for a future blogpost).

May this letter serve as an inspiration to our so-called public servants: country and family first, before the Self. And yes, conviction… but in the right place.

*F*I*L*I*P*I*N*O*e*S*C*R*I*B*B*L*E*S*

* “A voice crying out in the wilderness”, a reference to John the Baptist (Isaiah 40:3, Mark 1:3, John 1:23).

** A Spanish proverb which means a person’s fondness or attachment to one’s native land.

Reblogged this on Musings on education, teaching, lifelong learning and world events.

LikeLike

Thank you for reblogging this! 🙂

LikeLike

Señor Pepito, what are your thoughts in this? —> http://bit.ly/UgDoww <— 😀

LikeLike